Photo Gallery

WALLS IN TIMES OF PANDEMIC

“Walls in Times of Pandemic” – is an online exhibit that has been prepared with the contributions of many movements across the globe: from the Philippines to Mexico. It gives fragments of reality, traces connections and tells us what inspires these struggle.

Walls are symbols of exclusion, oppression, exploitation, discrimination and dispossession. In times of the COVID19 pandemic, lockdowns and quarantines, the walls that oppress and exclude have risen higher, become more brutal and more visible. Beyond these walls emerges a network of people and their aspirations that build a World without Walls.

This exhibit is part of the ongoing process of coming together of movements that started in 2017, when Palestinian and Mexican movements launched the call for a World without Walls, which by now is endorsed by over 400 networks, groups and movements from across the globe. 15 years ago Israel had started building its apartheid wall. Since then, the world has slowly adopted this paradigm, ushering in a veritable era of Walls. For a collection of reflections and stories of common action that have developed from that call see the World without Walls reader: https://book.stopthewall.org/

PHOTOS

Bethlehem, Palestien

Amjad Khawaja

This is the text author

Israel’s apartheid regime constructed the wall to spatially confine us in ever-smaller enclaves and separate ‘us’ from ‘them.’ Yet, we divert the wall from its intended goal of separation, and create new connections and meanings that challenge the structures of the occupation. We use the wall to honor and immortalize our martyrs who are killed by the Israeli occupation.

How has this wall changed during the pandemic?

Amid the spread of the pandemic and the intensified restrictions of the occupation, staging protests to advance our struggle or express our solidarity with other struggles is a real challenge. In Jerusalem, for instance, the Israeli occupation forces suppressed a rally to express rage at the murder of Iyad Hallaq, a Palestinian man with autism, and in solidarity with African Americans.

How do you resist the wall?

Now a mural of George Floyd has been added next to murals of our martyrs and prisoners and homages to struggles from India to Latin America. Through the mural of Floyd on the wall, we create a space to strengthen transnational networks of solidarity with our black sisters and brothers, not only in the US. Floyd’s mural on the wall stands for our linkage with all the struggles of the oppressed, those suffering under police brutality, those being exploited, enslaved, displaced and discriminated against. It is a linkage with the movements in struggle across the globe surpassing all set restrictions and boundaries.

The systematic, racist subjugation of Palestinians and black people and people of color serves to further solidify a system of white supremacy to other non-white ‘races.’ Thus, we believe that our struggle for liberation and self-determination intertwine with aspirations of self-determination and liberation across the world, where it can only thrive and flourish on internationalism and mutual solidarity.

Hong Kong

Trine Federis

Trine Federis

Housing is expensive here in Hong Kong. A two-bedroom flat’s (which in most cases, is more like one and a half) rent here can pay for at least four flats in Manila. Locals who qualify for public housing have to wait for years to be accommodated. To say that space is a premium here is an understatement. Stores, except the well-established ones, seem to exist in a flux. Here today, gone tomorrow. At least parks here are valued, compared to Manila of course. Rightfully so, in a place where space is scarce.

On Sundays, the usual hectic throng of office workers is replaced by groups of migrant domestic workers. The walkways that served as mere bridges to the next destination became centers of talk. The streets pounded six times a week by passing vehicles became spreads of familiar food. In a place where space is scarce, every bit of surface is given a new use.

How did the pandemic change it?

From the required live-in policy to discrimination in public spaces, migrant domestic workers often feel Hong Kong has no space for them. In a place where space is scarce, some make do with what is given to them. It can be said that Hong Kong has no place even for its poorer residents. With the push to privatize healthcare, more residents inevitably fall through the cracks. And as with all crises, like this COVID-19 pandemic, the marginalized sectors suffer the most.

How do you resist the wall?

To have space is to live. And if there is no space? We move things around. We make room. We act. In a place where space is scarce, freedom is brought by decisive action.

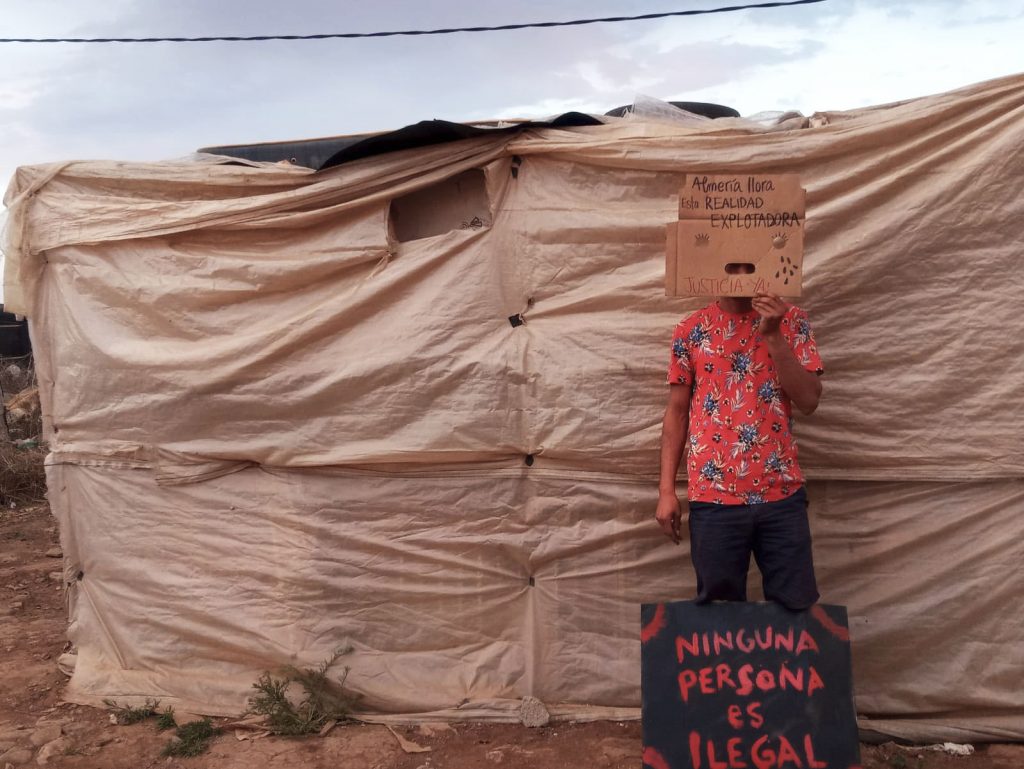

Comarca de Nijar, Andalucia, Spanish State

Ismail, activist in the campaign ‘Regularization Now’

Nadia Azougagh Bousnina

One more wall in southern Andalusia. A dividing line between the most atrocious capitalism of the intensive agriculture of the Almerian countryside and nature and the people who carry out this work essential to sustain life, not only their own.

We are talking about Almería, a province that has never seen great mobilizations, marked by a hostile socio-political character, with municipalities with both the highest per capita income and inequality and poverty in the entire Spanish state. Agricultural exports, supported by migrant labour, generate millions of euros while the workers are denied their most fundamental rights, such as the regularization of their status as migrants, labor rights, and access to decent housing.

Behind the ‘wall’ of the Nijar region there are more than 70 shanty towns where more than 8,000 migrants work in the fields to survive. Until recently there were only men. Currently there is a large increase in women living under plastic and wood in absolute vulnerability. Even the UN Rapporteur on Human Rights himself recently defined these shanty towns as worse than the refugee camps.

How did the pandemic change it?

The South has seen the lowest level of COVID-19 infections but is the place suffering the most from its socioeconomic consequences. Over the last 30 years (almost) nothing has changed. This ‘wall’ continues. Yet, the level of self-organization of those who suffer it has gained more force. The generation we have been waiting for has arrived and will be the ones who are going to fight this wall.

Barrios Carlos Mujica ex Villa 31, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Coordination of the Suburbs for a Real Urbanization

Arts Groups Tuca-Tuca

Villa 31 fights against a wall of exclusion and expulsion based on gentrification. One of the residents explains how the walls are built on a racist hatred: ”We are small, black, with indigenous traits and we live in a society where we are the ugly. This is what they make us feel and this government encourages it. It makes us feel like people with no right to anything, that we don’t deserve to be listened to, that we are nothing.” Last year, the city has issued a law that opens Villa 31 to urban speculation. She says, “The law is specific, it contains articles that are expulsive.”

How did the pandemic change it?

Silvana Olivera, militante del PXC (Peronismo x la Ciudad) e integrante del Comité de Crisis Villa 31, underlines that the ongoing policies of neglect and exclusion are particularly devastating during the pandemic. “None of the interventions of the city government are helpful. […] We ask that families be assisted so that they can quarantine in their homes with basic food. Because we know that today that nobody has food in their homes, to stay at home for fifteen days, this is unrealistic. Everyone here in the neighborhood survives on a daily basis and if you don’t work you can’t take a plate of food home.”

How do you resist the wall?

We as organizations are assisting the neighbors with what is lacking in hygiene: bleach, alcohol. What we manage to achieve through donations, but beyond the fact that we are organizations and we are predisposed to help, it is the State that has to give access to these things,” says Silvana at the eve of a press conference denouncing the wall of neglect and exclusion.

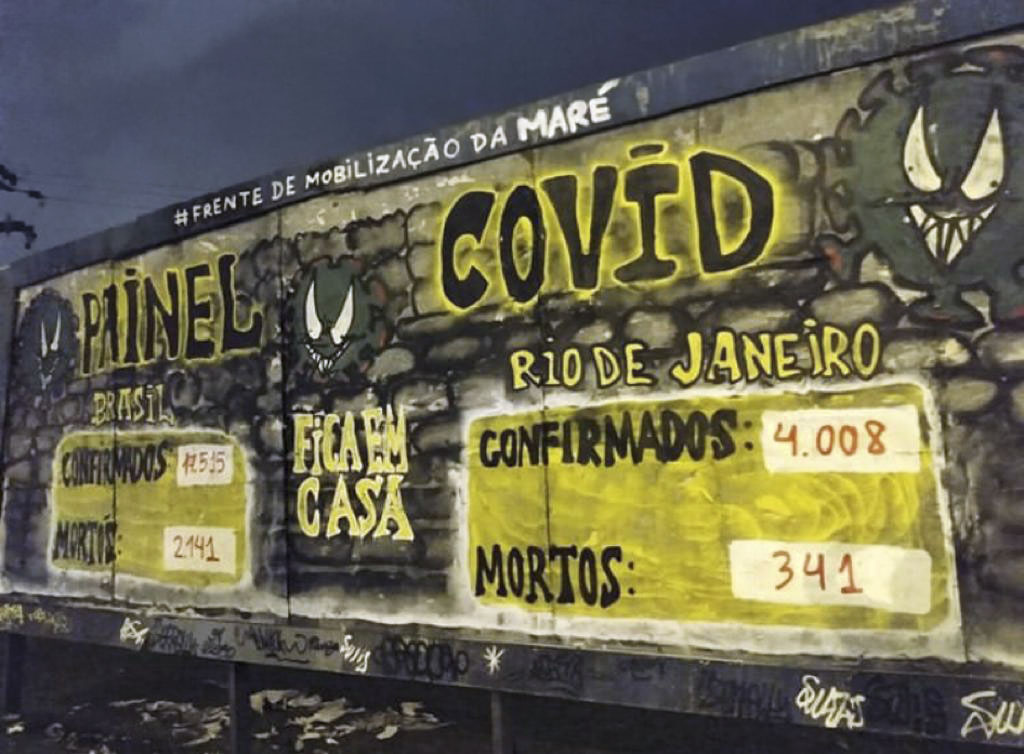

Favela La Maré, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Davi Marcos

Gizele Martins

We in Rio’s favelas are living left to our own, we are without water, without work, without food, and we are suffering from the constant attacks by the military and civil police. There are already countless black, poor, and favela children murdered within Rio’s favelas and peripheries this year. In the first four months of this year, more than 600 people, mainly young black people, were murdered in the favelas by the Brazilian government’s military and genocidal forces.

Because we are suffocated by this Brazilian policy of death and the worsening situation of the favelas, collectives that are part of Rio’s favela movement organized two demonstrations under the title: Black Lives Matter. Making this decision at a time of pandemic was necessary and urgent because we favela residents are seeing up close how our people die killed by gunfire, COVID-19 and hunger—the cruel reality of social inequality. Moreover, these same favela collectives have put a case in front of the courts demanding that, at least in this period of pandemic, no police operations will be carried out in our territories. The case continues in the justice system and if we win it, we would have achieved a momentary but momentous victory.

These same collectives in the territories where they live and struggle are carrying out efforts of awareness raising, delivering basic food baskets and also cleaning products so that the situation does not further deteriorate and the numbers of dead and infected by coronavirus do not continue to rise.

In other words, the walls of Brazilian social inequality, as well as the impoverishment of the Palestinian population and of all of Latin America follow similar patterns and increasingly we need to internationalize our struggles against the walls of social inequality, the walls of apartheid. It is our role to fight against the visible and invisible walls that separate our peoples. Our struggle must be united against states that spread terror among the population and make it ever harder for us to even survive, that threaten our lives and that of our peoples with weapons, invented wars, and racism. Let us internationalize the fight for our lives and history! Solidarity in the struggle!

Western Sahara

Mahfud Mohamed Lamin Bechri

Mahfud Mohamed Lamin Bechri

Fatimetu is from Western Sahara, she is 54 years old, and she lives in the liberated territory east of the wall that divides her land. She lives as a nomad ranching livestock close to the Moroccan wall. When she was 30 she lost her leg after a landmine explosion. The Moroccan wall in Western Sahara is known by Saharawi’s as the “wall of shame” and it contains more than 7 million anti-personnel landmines that put Saharawi lives at risk in a daily basis. Fatimid said, “I thank God that I only lost my leg, the accident was tragic and I didn’t expect I will have a chance to live after it.” The wall also threatens the life of animals. “Every day we see camels, goats, and sheep injured and losing parts of their body due to mine accidents and as we don’t have veterinary facilities, these animals lose their lives,” said Fatimetu. (see attached picture).

How did the pandemic change it?

As nomads, we rely on our livestock and because of the drought of this year we are obliged to use vehicles to bring water from wells and also feed to our livestock from neighboring countries (Algeria and Mauritania) as the wall and the state of occupation is impeding us to get it from the other part of our country,” said Fatimetu. The health crisis of COVID-19 and its fast outbreak has changed everything. “Since March of this year, all boarders were closed and we couldn’t access neighboring countries to get feed for animals or fuel for our vehicles. We are losing our livestock on a daily basis. The situation is dramatic,” added Fatimitu.

How do you resist it?

We, the Saharawis are having a very brave battle, a battle against occupation, against a wall that divides our land and our people, against mines that take lives of our beloved ones and also of our livestock and now COVID-19 and its fast outbreak has become another heavy battle for us,” with tears in her eyes, Fatimetu spoke. Fatimetu and other Saharawi women have a big role in the Saharawi plight, they are very active in building and maintaining the Saharawi institutions both in the liberated territories of Western Sahara and in the refugee camps in Algeria. She is very active in denouncing the crime of the wall and despite her disability she is present at all nonviolent actions against the wall and occupation. “Despite everything, we are a courageous people, a strong woman, and we believe that we will overcome all this. We will never give up and we will continue our fight until we get our rights, our legitimate right to self-determination and independence and this wall will be removed one day, I’m sure,” concluded Fatimetu.

Syria/Philippines

Rey Assis

Rey Asis, Asia Pacific Mission for Migrants

All I could remember was that it was on the ground I was standing on one hot afternoon in 2003 when my Syrian friends brought me to Syrian Golan, or what is left of it. All around me was rubble, bricks that used to be ceilings, memories of beautiful smiles on children’s faces before their homes were bombed by their “neighbors.”

Whenever I become complacent, I look for this shard of glass to remind me that wars of occupation and aggression continue to rage, building walls between people, between their dreams of having their own sovereignty, their country, the right to live in just peace.

Bakersfield / Berkeley, California, USA

Mesa Verde Detention Center (left) by Juan Prieto; Faith Leader Heart (right) by Theo Rigby

Rev. Dr. Allison J. Tanner, faith leader with Interfaith Movement for Human Integrity and a pastor of Lakeshore Avenue Baptist Church, Oakland, California.

The U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency functions to criminalize immigrants, migrants and refugees. It is an extension and expansion of the massive carceral system in the U.S. that disproportionately imprisons black and brown bodies. ICE detention is unjust, inhumane and completely unnecessary. The ICE abolition movement seeks to topple the racist and xenophobic walls of ICE detention, in partnership with projects to destroy all walls that promote mass incarceration and limit mass migration.

ICE detention ensures second-class treatment of immigrants, migrants and refugees, overly and often doubly punishing those who are denied citizenship rights. They are notorious for their inhumane treatment of detainees: filthy facilities, lack of sanitation and hygiene supplies, lack of medical care, forced labor, and limited communication with loved ones. These conditions have worsened under COVID conditions: spreading sickness through transfers and not testing guards, failure to provide masks and soap, and the inability to social distance, resulting in the reality for many that detention has become a death sentence. Two detainees have already died from COVID.

ICE detainees protest their deplorable and deadly conditions through organizing hunger strikes, demanding dignity, communicating their human rights violations with the outside community, and strategizing with their attorneys options for release. Attorneys, activists, and faith leaders are hard at work pushing for their release and using this COVID moment to further demonstrate the inhumanity of ICE practices. Together, we’ve been able to release hundreds of detainees to their families, their communities, and sometimes to local congregations who provide shelter, accompaniment, and sanctuary. One by one, detainees are gaining freedom and we are working together to destroy ICE’s racist and xenophobic walls.

The photos below send a powerful message of solidarity between ICE detainees at Mesa Verde Detention Facility (Bakersfield, CA) and faith leaders in the Bay Area (Berkeley, CA). Placed side by side, families are united and community is restored. Over the past four months, ICE has been required to release hundreds of inmates. We continue to fight for the freedom of all who are still imprisoned.

Tulkarem, Palestine

Manal Shqair, Stop the Wall Campaign

Manal Shqair, Stop the Wall Campaign

At three o’clock in the morning around 20 thousand Palestinian workers queue for hours in the cage-like Israeli military checkpoint of Taybeh. It is one among other checkpoints across the occupied West Bank through which Palestinian workers have to pass to reach their work in Israeli corporations every day.

To avoid the over-crowded cage, some workers even arrive in the place at 12.30 AM. Yet, the long process of inspection still makes those who arrive earlier wait for hours. All the 20 thousand workers go through inspection machines that show the smallest details of their bodies to Israeli military on a screen. Yet, this does not suffice in deciphering the bodies of Palestinian workers for ‘security’ reasons, as the occupation authorities claim. Israeli inspectors take many workers to inspection rooms where they have to be unclad in front of the inspectors.

This process of inspection is yet another way to humiliate Palestinians and consolidate their systematically constructed sub-humanness, otherness, and inferiority.

How has this wall changed during the pandemic?

When the COVID-19 pandemic spread, the Israeli government ensured continuous growth of its economy by continuing to exploit Palestinian workers. Despite the pandemic, workers still have to wait for hours at checkpoints where social distancing as a preventive measure is simply impossible. In the workplace, no protection is given to them.

How do you resist this wall?

The Israeli occupation is based on and feeds a capitalist and Neo-liberal system that exploits Palestinian workers. The plight of Palestinian workers and other workers around the world are interconnected in this basic process. The unity of workers’ struggle is essential to strengthen the collective power of the people to defy the tyranny of exploitative systems reaping the profits from the backs of workers.

Hong Kong

Jen Cabañez

Jen Cabañez, Organic Environmental and Cultural Migrant Organization

Despite the contribution they make to economy, migrant domestic workers are continuously being undervalued. The government’s negligence to our needs is apparent. We are treated as commodities, not people. We are treated as slaves, not workers.

Such treatment put a wall between us and them, and a wall to recognition of our worth and more importantly to a dream where we all can live decently, and slavery is a thing of the past.

Tijuana, Mexico

Gilberto Conde

Soraya Vasquez, Al Otro Lado AC

The pandemic exacerbates the humanitarian crisis on this border, the wall becomes an accumulation of laws and restrictive measures that blur asylum. In the endless waiting fear, anxiety and despair also spread [are also contagious?]. The suffering of families is the other pandemic.

Governments have abandoned migrant families to their fate. We civil society organizations resist, we move to models of remote [distance] care, we provide humanitarian aid to meet the basic needs of those who have nothing, we continue to accompany their processes and fight for the human right to migrate. Nobody here gives up.

Lesvos, Greece

Lorraine Leete – Legal Center Lesvos

Lorraine Leete – Legal Center Lesvos

Here, in a photo taken from Lesvos island on 17 June 2020, two Greek vessels surround a migrant boat, which GPS coordinates confirmed was in Greek water. For several hours, the migrant boat was left without assistance. The Turkish Coast Guard later collected the occupants of the boat, returning them to Turkey. Collective expulsions carried out in this manner are contrary to international law, violate individuals’ right to life, right to be free from cruel and degrading treatment, and are in violation of international maritime law obligating rescue at sea.

How did the pandemic change it?

On 1 March 2020, Greece suspended the right to seek asylum, and announced that it would fortify its borders to prevent entry of migrants travelling from Turkey. While the right to seek asylum has technically been reinstated, the 1 March announcement was followed by the Greek state’s adoption of various practices in violation of migrants’ rights, which continue to date, including the violent fortification of Greece’s borders, growing numbers of collective expulsions from Greece to Turkey, and the mistreatment of those who do reach Greece from Turkey.

How do you struggle against it?

Direct testimonies from victims, collected by the Legal Centre Lesvos, demonstrate the collective expulsions occurring in the Aegean region are systematic, and have clear modus operandi that are implemented by various Greek authorities, across various locations in the Aegean and on the Eastern Aegean islands.

Hong Kong

Rey Assis

Rey Asis, Asia Pacific Mission for Migrants

Now, she is back “home.” But where is home really for a migrant? While it can also be a choice, migration has become a forced decision for people to survive, to leave their families behind so they can put food on the latter’s tables and hopefully, to give them a better life.

Migrants’ lives are filled with invisible walls that hinder them from fully realizing their dreams, from being recognized as people.

Manila, Philippines

AG Sano

Tetet Nera-Lauron

“Darna” is a fictional character and Filipino comics superheroine beloved by many for generations. She symbolizes strength of character, putting herself on the line to combat evil and to do good, and proving that disability is not a hindrance in serving humankind. The image of Darna in scrubs painted on a wall is very symbolic—an act of defiance to the powers-that-be, and hope-inspiring for the Filipino people in these very trying times.

The Philippines is enduring the combined effects of having the world’s longest lockdown (even longer than the 76-day lockdown of Wuhan, China), an inept and unaccountable government that has adopted a militarist approach as its COVID-19 response, and multi-layered inequalities resulting from the continuing legacy of colonialism. The lockdown has been disastrous to millions of poor Filipinos as restrictions have made it hard to find livelihood sources and food, making many families dependent of inadequate and dwindling state rations. More than 100,000 people have been arrested, tortured, or killed for violating quarantine (being outside when they shouldn’t be or in a community which isn’t their own), while government officials and other VIPs are given a mere slap on the wrist for partying and traveling.

The government has used the pandemic to silence opposition with its clamp down on independent media and critical voices. The Philippines largest broadcast station was shutdown, an internationally-acclaimed journalist charged and found guilty of cyberlibel, and an Anti-Terror Law was hurriedly approved by Congress. But despite these developments, Filipinos are finding strength in our collective resistance and solidarity with each other. We will persist. We will continue to resist.

Bir Nabala, Palestine

Manal Shqair, Stop the Wall Campaign

Manal Shqair, Stop the Wall Campaign

In this picture, where a group of people stand in the town of Bir Nabala, northwest Jerusalem I once stood like them eight months ago. There, I contemplated the wall. I could see in it a giant monster in total control of our spatial and temporal presence in our homeland.

The people who used to live in the houses close to where the wall is built are no longer living there.

How has this wall changed during the pandemic?

I was told that the owners of the deserted houses had to move to Jerusalem to live in populated areas so that their children can access the schools they used to attend before the wall was constructed. They might have been going through hard times like other Palestinian Jerusalemites since the spread of the pandemic. The Israeli occupation treats Palestinians in Jerusalem as the excluded presence by denying them access to proper medical care and protective measures amid the spread of the pandemic, compared to the Israeli Jews living in the city.

How do you resist the wall?

Yet, as the Israeli occupation denies us our past and present, we should never allow them to deny us imagining a better future, where the wall is dismantled, the owners of the forsaken houses are back, and Jerusalem is no longer a place of discrimination and exclusion of Palestinians. It might sound like an impossible and infeasible imagination. Yet, as a people subjugated by a settler colonial and apartheid regime, we are the ones to determine what is feasible and rational in the imagination of our future, a future of justice without walls and any other means of racial segregation which keep reminding us that in our own native land we are the ‘other.’

Militarized/occupied O’odham lands near A’al Waippia/Quitoboquito Springs in the Organ Pipe National Monument Park, in Arizona, USA.

Conor Handley and the Wui Ke:kiwan Hemajkam (People Standing Together), January 2020

Amy Juan

The US Mexico Border, established by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) and the Gadsden Purchase (1854), has divided O’odham lands and Peoples in half since its creation. The Indigenous Peoples of this land were never consulted when the line was drawn, and to this day are not considered equal partners in the ongoing building of militarized infrastructure. This border has changed the lives and history of the O’odham by creating barriers of movement across the border for O’odham in both Mexico and The United States. O’odham in Mexico do not have access to healthcare, education, and in most cases running water or electricity, and have throughout the years crossed the border with no problems to receive the care they are afforded as members of the Tohono O’odham Nation. Also, many O’odham in the United States would cross the border for ceremonial and religious purposes, as well as to remain connected with family and sacred landscapes.

For many years the border remained a barbwire fence, but after 9/11 has changed drastically to be one, if not the most militarized Indigenous community in the United States. The border has since been reinforced by Normandy-style steel barriers, Integrated Fixed Towers courtesy of Israel’s military company Elbit Systems, and now a physical border wall. The Tohono O’odham Nation also has two forward operating bases occupied by the US Border Patrol, on the ground patrols and surveillance and checkpoints to every entrance and exit of the Tohono O’odham Nation.

In January 2020, young O’odham mobilized to protect the sacred A’al Waippia/Quitoboquito Springs, which has existed in the harsh desert for over 16,000 years and is home to some of the rarest endangered species such as the Sonoran Mud Turtle and Sonoran Pupfish, as well as the Spring Snail, which is the size of a poppy seed.

The onslaught of the construction of Trump’s border wall in drastic measures during the pandemic, has border wall workers pumping water from nearby aquifers to mix concrete for the wall heading towards Yuma, Arizona. Since January, the spring has drastically receded and dried up. Currently members of the community are establishing a camp onsite to protect the spring from further destruction.

Katatura, Windhoek, Namibia

Koni Benson

Koni Benson, Asher Gamedze, Nashilongweshipwe Mushaandja

The piece on the wall pictured in the image was taken at Jakob Marengo High School in Katutra, Windhoek. The wall’s first paintings, in 2019, was the culmination of a number of years of organising across various spaces in Southern Africa through art, history and education work all within the broader project of liberation. Since 2016 we have been building community to collaborate on projects that attempt to bring together these (usually) separate practices through workshops that try to creatively deepen a radical historical imagination beyond national as well as disciplinary borders. Experimenting towards a post-border praxis is our response to the histories and contemporary political crises of borders. Through this work of historicizing and challenging borders we attempt to participate in and contribute to movements in our own context and elsewhere imagining liberatory futures and building them.

“Radical Imagination is the Future” was painted on a school wall at the end of a collective mural making session with art college students, high school students, historians, and activists during a decolonial arts praxis festival, called Owela. It followed on from a Youth Without Borders study tour across South Africa, Botswana, and Namibia the year before, where the founder of the school Ottilie Abrahams had shared the history of school, in the context of her life history. Aunt Tilly was involved in feminist and socialist movements from the time she was a teenager and joined underground reading groups in Windhoek and in Cape Town in the 1950s, to the time she was part of initiating SWAPO, running their education camps in Tanzania, to the time she was expelled for challenging corrupt leadership and donations that planted seeds of division.

Returning after 16 years in exile with southern African liberation movements in Zambia, Tanzania, and Sweden, Ottilie Abrahams founded the Jakob Marengo Tutorial College- a school for liberation run on the principles of participatory democracy, critical thinking, and non-sexism. The school was named after the leader of a Nama and Herero alliance against German colonists between 1904-1908. Jakob Marengo, the school, was initiated in opposition to Bantu Education in Namibia. Namibia was until 1990, ruled by apartheid South Africa as inherited from German colonists after WWI. It was treated as a Bantustan, with the name South West Africa. Challenging colonial borders and creating worlds without walls was key to the school from the start. Aunt Tilly recalled: “When we started Jacob Marengo, a quarter of our students were from South Africa where schools were burned down–highly politicized children; and the other group came from northern Namibia, where the secondary schools had to operate under the watchful eyes of the occupying forces. So we saw our job as preparing children for an independent state, for the development of the country.” From 25 students in 1985, today the school last year had over 1000 children. About half the students come from Angola, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo and struggle to be admitted to ‘’local schools.” Because…the past is not history and the present requires radical imagination to take us forwards into a future without borders.