Fidel Castro’s passing has been for many a moment of reflection on Cuba’s past and present. In this article published by the Afro-Middle East Centre, we revisit the Cuban revolution’s contributions to peoples’ struggles across the globe and to the Palestinian people in particular. As many movements around the world are grappling to understand, redefine and practice contemporary and effective forms of internationalism and solidarity, a look at this history and at present-day efforts may help to identify new inputs to shape global connections among peoples.

By Maren Mantovani

By defending their national rights the Palestinian people have defended the rights of all revolutionaries in the world and the blood spilled by their sons is like the blood of our peoples. (Fidel Castro, 23 August 1982[1])

Fidel Castro’s passing has been for many a moment of reflection on Cuba’s past and present. We want to revisit here the Cuban revolution’s contributions to peoples’ struggles across the globe and to the Palestinian people in particular. Firmly convinced about the necessity of internationalism, Cuba played a key role in strengthening concepts of solidarity, bringing peoples together and supporting liberation struggles all over the Americas, Africa and Asia. For the Palestinian people, Cuba has been an important ally for decades and the gateway to the liberation movements in Latin America.

Today, as many movements around the world are grappling to understand, redefine and practice contemporary and effective forms of internationalism and solidarity, a look at this history and at present-day efforts may help to identify new inputs to shape global connections among peoples.

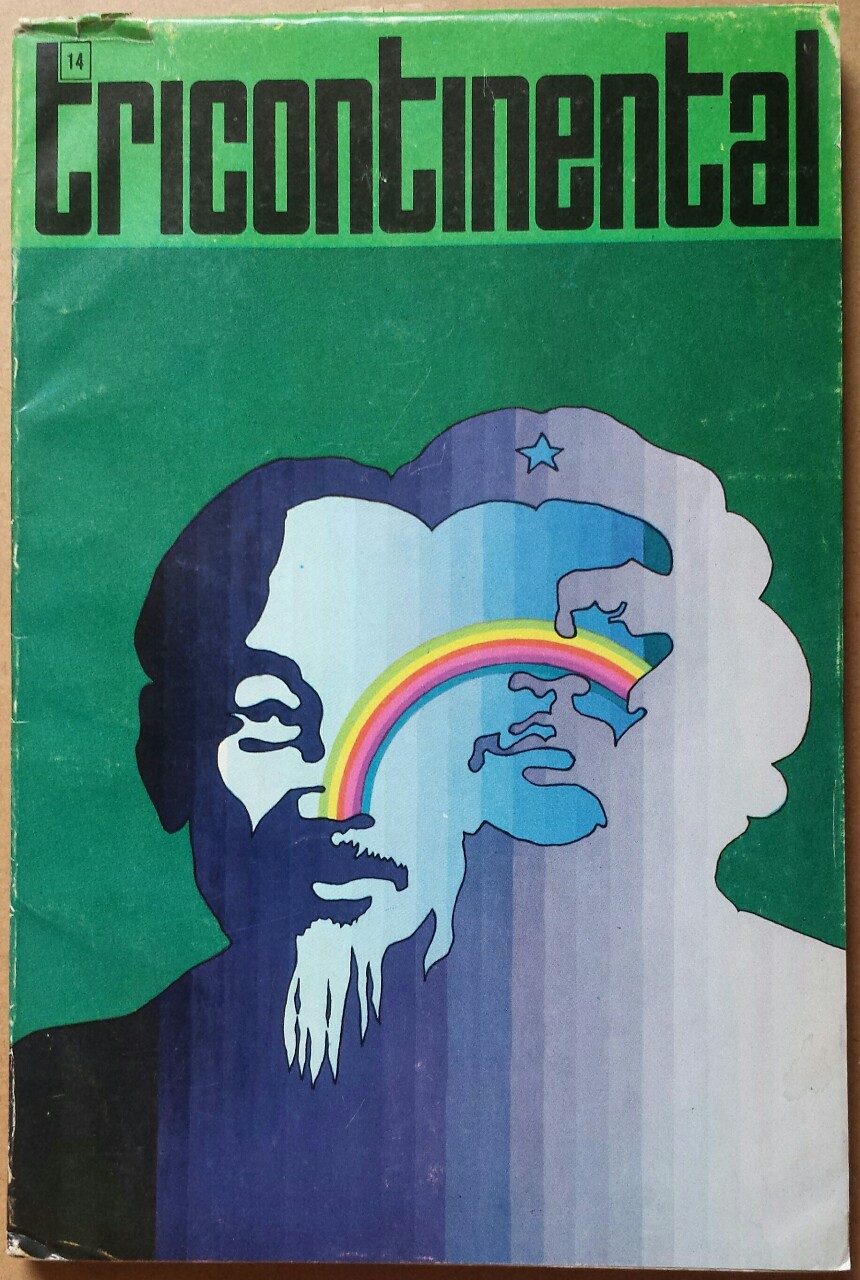

Palestine and Cuba’s Tricontinental Conference

In the first decade since the Nakba ('catastrophe' in Arabic), when Israel’s formation in 1948 meant the expulsion of the majority of the Palestinian people from their homeland and the transformation of the Zionist movement’s settler-colonial aspirations into a state based on apartheid, ethnic cleansing, occupation and aggression, the Palestinian people had two central tasks to complete. On the one hand, they had to organise resistance structures; on the other they had to create awareness about the existence, rights and motivations of their struggle, countering at the same time the notion that expelling the Palestinian people from their homeland and creating a new colonial regime on Palestinian land could somehow be justified as reparation for the Nazi holocaust. In less than a decade the PLO achieved an incredible feat – establishing concrete and solid relations with peoples, governments and movements from Asia to Latin America. The efforts of these years ensured that until today a large majority of the world’s governments support Palestine, even if only nominally during UN voting sessions. This would have been impossible if not for the support of some of the leaders, governments and movements that shaped the world in those days.

Arab leaders, most importantly the Egyptian president Jamal Abdel Nasser, India’s Jawaharlal Nehru and the leadership of the People's Republic of China were among the first to help put the Palestinian cause on the agenda of the Non-Aligned Movement and socialist countries, elevating it to a central struggle embodying anti-colonial and anti-imperialist aspirations. Their support ensured strong ties with Asia. Palestine’s breakthrough in Africa started with support from Nasser and Algerian prime minister Ahmed Ben Bella in the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). Founded in 1963, the OAU was central in supporting African liberation movements against colonialism. The existence of close ideological, military and economic ties between apartheid South Africa and Israel, both using apartheid as a framework to preserve a settler colonial regime in the twentieth century, and direct relations between the African National Congress and the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) strengthened support for the Palestinian people throughout Africa.

The Palestinian people’s entry to Latin America was largely due to support received from Cuba, in particular during the Tricontinental Conference held in January 1966 in Havana. The Palestinian people played an often forgotten role in the construction of this historic event, which brought together more than 500 representatives of eighty-two delegations.[2] Linking the experience of the Non-Aligned Movement and socialist and national liberation struggles in the global south, it bridged the geographic and ideological divides between revolutionary movements in Latin America and African and Asian anti-colonial struggles and governments. Amongst the delegates were leading figures such as Fidel Castro, Salvador Allende and Amilcar Cabral. It was in fact in Gaza that the celebration of a tricontinental conference was agreed upon. In 1961, the Palestine Committee for Afro-Asian Solidarity[3] hosted a meeting of the Afro-Asian Solidarity Organisation, linked to the Non-Aligned Movement. The meeting, held in Gaza as a sign of solidarity with the Palestinian and Arab people, made significant steps forward in the construction of the Tricontinental Conference.

The First Tricontinental Conference opened up Latin America to the Palestinian liberation movement. A sizable delegation of Palestinian representatives from various PLO factions participated and presented the case of Palestine. They forged solidarity ties and further developed their understanding of Latin American struggles.

Defining solidarity: The tricontinental spirit

![]() Once gathered in Havana, the delegates developed what became known as a ‘tricontinental spirit’. They were imbued with a sense of urgency to form, in the words of the conference declaration, a unique alliance against the ‘system of oppression and exploitation of colonialism, neocolonialism and imperialism’[4] and to devise effective forms of cooperation. At the time, debates on solidarity centred on the Vietnamese people’s resistance; however, the Palestinian struggle had an outstanding place even then. The Tricontinental Conference’s final declaration called specifically for ‘solidarity of all peoples with the Arab people of Palestine in its just struggle for the liberation of its homeland from imperialism and Zionist aggression’.[5] Just as the Palestinian cause was a fundamental part of the tricontinental spirit, the PLO considered its struggle a part of global anti-colonial and anti-imperialist efforts. PLO chairman, Yasser Arafat, in a 1969 visit to Cuba declared:

Once gathered in Havana, the delegates developed what became known as a ‘tricontinental spirit’. They were imbued with a sense of urgency to form, in the words of the conference declaration, a unique alliance against the ‘system of oppression and exploitation of colonialism, neocolonialism and imperialism’[4] and to devise effective forms of cooperation. At the time, debates on solidarity centred on the Vietnamese people’s resistance; however, the Palestinian struggle had an outstanding place even then. The Tricontinental Conference’s final declaration called specifically for ‘solidarity of all peoples with the Arab people of Palestine in its just struggle for the liberation of its homeland from imperialism and Zionist aggression’.[5] Just as the Palestinian cause was a fundamental part of the tricontinental spirit, the PLO considered its struggle a part of global anti-colonial and anti-imperialist efforts. PLO chairman, Yasser Arafat, in a 1969 visit to Cuba declared:

The alliance of the Arab and Palestinian national liberation movement with Vietnam, the revolutionary situation in Cuba and the People's Democratic Republic of Korea and the national liberation movements in Asia, Africa and Latin America is the only path to create a camp that is capable of confronting and triumphing over the imperialist camp.1

In his letter to the Tricontinental Conference, Che Guevara pointedly stated: solidarity ‘is not a matter of wishing success to those who are being attacked’.[6] This call for concreteness in action was a core element of the meeting. The encounters in Havana strengthened Cuban–Palestinian ties and set the basis for concrete cooperation between the PLO and liberation struggles in Latin America. Since then movements, such as the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front in El Salvador, the Sandinista National Liberation Front in Nicaragua and the Montoneros in Argentina, maintained close relations with the PLO. Latin American militants fought together with the Palestinian movements, and Palestinian movements trained and provided weapons for national liberation struggles in Latin America. The Sandinistas’ spokesperson Jorge Manda stated in an interview in 1979:

There is a union of blood for a long time between the Palestinian revolution and us. Many of the units of the Sandinista movement have been in Palestinian revolutionary bases in Jordan. In early 1970, Palestinian and Nicaraguan blood was spilled together in Amman and elsewhere during the Black September battles.[7]

At the official, diplomatic level, relations forged and strengthened during the Tricontinental Conference yielded important fruits. Cuba became one of the most outspoken supporters of the Palestinian cause in international fora. Cuba co-sponsored UN Resolution 3379, which defined Zionism as ‘a form of racism and racial discrimination’, based on existing resolutions of the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organisation for African Unity. During the 1960s and 1970s, many countries from the global south broke diplomatic ties with Israel.[8]

Already in the first years of the PLO’s existence, the Palestinian struggle became a symbol of resistance and inspiration for progressive, left and social justice movements across the entire global south and, by the end of the 1960s, the movement had built increasing ties in Europe and North America as well.

Re-encounters at Durban’s World Conference against Racism

Unfortunately, the 1990s saw a weakening, if not collapse, of many efforts to build global solidarity among peoples struggling against colonialism, neocolonialism and imperialism. The collapse of the socialist bloc dealt an almost fatal blow even to the idea of non-alignment, and global anti-capitalist struggles faced dramatic challenges. US and European interventions broke down the last remnants of Arab nationalism. For the Palestinian people, the Oslo ‘peace’ process period mediated by the USA and Europe reflected a new paradigm: Left without almost any safe haven in the Arab world, and at the start of a decade where the West dominated a unipolar world order, Palestinian movements focused much of their international relations on western states.

However, by the year 2000 it was clear that no ‘Pax Americana’ would arise anywhere, let alone in Palestine: Military aggression, not only in the Arab world, continued to increase and, instead of creating a Palestinian state on the 1967 borders, Israeli settlements had dramatically increased in the occupied West Bank, stealing ever more Palestinian land and resources, and accelerating ethnic cleansing policies in the Palestinian territories. In September 2000, yet another Palestinian popular uprising, the second intifada, erupted and was drowned in blood only in 2002 when when the Israeli forces conducted large-scale military operations in the occupied West Bank and began building an eight-metre high apartheid wall, stretching more than 700 km in length and encircling Palestinian villages and cities. Israel literally cemented on the ground its plans for a final status solution for the Palestinian people in form of a Bantustan system, akin to the South African apartheid regime’s attempt to contain the black population in isolated reservations. For many years, Gaza has been an open-air prison, while Israel continues inflicting ethnic cleansing policies against the Palestinian population in roughly sixty per cent of the occupied West Bank. The right of return of the refugees, which make up the majority of the Palestinian population, seems further away from implementation than ever, and Palestinian citizens of Israel suffer increasing racial discrimination and displacement. The Oslo period’s end has thus created an urgency to develop new strategies and recover fading alliances.

For Palestine, the 2001 World Conference against Racism in Durban came at the right time to bring back centrality to a global south country – South Africa – and to revive an almost abandoned argument on Zionism’s racist nature. The grassroots movement’s decision to define Israel’s infrastructure project as an apartheid wall must be situated within this framework.

The re-encounter with South Africa and its anti-apartheid movement’s legacy strongly inspired the Palestinian call for boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) issued on 9 July 2005 by over 170 Palestinian organisations from all across the historic homeland and the diaspora. Uniting all Palestinian political parties and major unions and networks, this call created once again a cohesive strategy for action at an international level. The rationale of the BDS call is basic: A capitalist and colonial enterprise will only survive as long as it creates profit. As a direct response to the failure of the US and European governments to ensure a just solution for the Palestinian people, the BDS call is a call to the people across the world who share a common goal of fighting injustice, oppression and exclusion. It is a call to governments that respond to the voices of their people or, at the very least, are not intrinsically beholden to Israel.

The context of a tricontinental spirit of the twenty-first century

Fifty years after the Tricontinental Conference, the context in which internationalism operates has changed dramatically. While Cuba remained a reference throughout this time, and the Palestinian struggle remained a global symbol of resistance, resilience and hope for social justice struggles, in most of the countries that at that time supported the Palestinian people, the celebration of neoliberal trade and investment agreements superseded solidarity ties. Movements that once stood side by side with the Palestinian people, and received Palestinian support and training, have in the meantime come into power and favour Israeli investment over historical legacies.

These shifts in positioning of national movements and governments reflect the demise of anti-colonial aspirations as an achievable aim for states as well as economic transformations. Never before in history has transnational capital had such sophisticated institutions and regulatory frameworks protecting and implementing its interests. This does not mean the end of the role of state power but shapes it differently in the face of transnational capital, which is deeply linked with national governments and state institutions. Over the last decades, this understanding permeated movements across the globe, and therefore, they began dedicating significantly more focus in their struggles to targeting these corporate structures and interests.

Another landslide shift occurred with the growing space held by ‘emerging’ economies in Asia, Africa and Latin America in terms of world trade and global GDP. In 2015, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) alone accounted for a total nominal GDP of 16.92 trillion, equivalent to 23.1 per cent of global GDP,[9] equal to the EU’s share. The BRICS share in global exports rose from eight per cent in 2000 to nineteen per cent in 2014.[10] Over the last decades, transnational corporations formed based on capital in the BRICS countries. This theoretically gives emerging economies much greater potential for economic and political leverage. However, in fact this development has in no way overcome imperialist and colonial structures: The peoples of Africa, Asia and Latin America still pay the price for colonial and imperialist exploitation. Western states, including Israel, and their transnational corporations continue to reap the key profits from the system. The people in Asia, Africa and Latin America remain caught in proxy wars and brutally repressed whenever they rebel against the system. Israel in this context acts not only as an imperialist stronghold in West Asia but in the era of the ‘global war on terror’ has turned into the world’s most profitable laboratory and exporter of concepts and technology of repression and Orwellian systems of surveillance.

The Israeli military–industrial complex, which fuels and profits from Israel's wars of aggression and repression, has always been dependent on exports for its survival. Today it exports up to eighty per cent of its production.[11] Between 2010 and 2015, eight of the ten major importers of Israeli weapons were in the global south, including India, Turkey, Singapore, Vietnam, Colombia and Brazil.[12] In 2013, Israel exported almost US$4.8 billion worth of arms to Asia, Africa and Latin America, while only US$1.7 billion went to North America and Europe.[13] Created after the 1967 war, the Israeli military industry’s first customers, which provided vital input to the industry, were Central and South American dictatorships that used weaponry to repress the liberation movements with which the PLO had cooperated since the Tricontinental Conference. Today, Israel continues to reap profits from repression and genocide in Latin America and beyond. In Rio de Janeiro, Israeli trainers pass on their knowledge to some of the most brutal police squads on the planet.[14] Israel was directly involved in the Rwandan genocide.[15] Security and military cooperation between India and Israel has exacerbated existing communal conflicts through anti-Muslim propaganda and provision of weapons[16] and training[17] to repress the Kashmiri movements in their quest for self-determination.

In addition, the global south is playing an ever-growing role in sustaining the Israeli economy via civilian trade. The 2008 economic crisis and victories of the growing Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement in Europe have both contributed to limiting the profits Israel can reap from economic relations with Europe. Over the last five years Israeli exports to the USA have shrunk by US$ 342 million, making the USA the Israeli market that shrunk more than any other in terms of net value of exported goods.[18] Many EU countries have negative growth rates for imports from Israel as well. As a result, Israel’s financial establishment has looked towards the global south, especially Asia. Leo Leiderman, chief economist at Bank Hapoalim, stated: ‘Israeli exports to emerging markets account for about thirty-six per cent of total exports of goods, similar to emerging markets’ share of global trade…Asian markets, headed by its two giants, China and India, have paramount importance for Israeli export growth in the coming decades.’[19]China is already Israel’s third biggest export destination and India the seventh. Both countries are currently negotiating free trade agreements with Israel. With 14.37 per cent of total Israeli imports (excluding diamonds) coming from China, Beijing ranks number one, even before the USA with 13.42 per cent, as a source of Israeli imports.[20] The BRICS countries together are the source of 20.7 per cent of Israel’s imports.[21] All BRICS countries have had rising annual growth rates of Israeli exports over the last five years. Today, Israeli exports to Asia exceed the value of exports to Europe.[22] Among Israel’s top ten export items are medicine, cell phones, fertilizers and medical instruments – products for which Africa, Asia and Latin America offer huge markets.[23]

Tricontinental solidarity today

This confers renewed tricontinental solidarity an unprecedented opportunity and responsibility. While these efforts and struggles cannot be disconnected from the struggles in North America and Europe the shared position and experience within Asia, Africa and Latin America defines a natural common ground.

One common ground can be found, as said, in the growing focus among social justice movements to hold transnational corporations to account for their infringements of people's rights. The struggles and victories of communities defending their lands and livelihood against mining corporations, such as Glencore International AG[24], mega-projects such as the Agua Zarca dam in Honduras[25], or multinationals destroying natural resources such as the struggle against Coca-Cola in India[26] tell stories of popular uprisings successfully impeding, delaying or increasing the costs of construction and operations of transnational capital. Local protests, international pressure, legal struggles and efforts to defund these devastating projects by targeting the banks that give the loans to the corporations are shared tools developed by people to defend their rights and hold corporations and complicit governments responsible.

The Palestinian call for boycotts, divestment and sanctions – to stop impunity not only of the Israeli state but also of all corporations and institutions that profit from or sustain Israeli apartheid – mirrors such struggles. Victories against transnational corporations such as Veolia, which lost over US$20 billion in unsigned contracts and suffered several divestments from financial institutions before it quit operations in Israel, is one example.[27] Another case in point is the growing number of victories against G4S.[28] The global ‘security’ giant, now under pressure from movements across the globe, provides not only vital equipment for the Israeli prison system and military checkpoints but also is involved in mercenary services in Iraq and Afghanistan,[29] and holds the security contracts to guard the Dakota Access Oil Pipeline against which indigenous people and social movements have launched a fierce struggle to defend their land and resource rights.[30]

Probably the best example of how campaigns in support of the Palestinian struggle and its call for boycotts, divestment and sanctions target not only Israeli policies against the Palestinian people but also global structures of oppression is the ‘Stop Mekorot’ campaign.[31] Israel’s national water corporation Mekorot is a key agent in the theft of Palestinian water, which simultaneously ethnically cleanses Palestinian communities by forcing them to abandon their living spaces due to lack of access to water and enables the colonisation of the land by Israeli illegal settlements, to which Mekorot provides water. Since it began international operations a decade ago, the company has profited from water privatisation across the globe. Its contract for a water desalination plant in La Plata, a province of Buenos Aires, which Palestine solidarity campaigners together with trade unionists defeated, highlights not only that the project violated the Palestinian BDS call but more importantly would have exported Israeli water apartheid to Buenos Aires, offering drinking water only to the rich districts and raising prices for consumers unnecessarily.[32] In India, Israel’s proclaimed ‘support’ to the agricultural sector upon closer inspection also comes at a high to cost small- and medium-sized farmers. Israeli Elbit Imaging, for example, has been involved for many years in largely failed and damaging dairy projects, importing foreign breeds in order to industrialise and concentrate the sector under the control of large-scale agro-business enterprises. A report by the Global Forest Coalition on these practices tellingly concluded that: ‘Instead of blindly promoting foreign breeds, the government should support livestock keepers in improving their animals’ food, water and other conditions. The success of the Indian Gir breed in Brazil could provide some inspiration in this regard.’ [33] Movements across the world are finding similar ways to target the oppressor, which unsurprisingly often end up to be the same – controlled by the same capital or employing similar methods.

Especially in the last decades, movements have tried to build new spaces in which to exchange ideas and experiences – ranging from the Intergalactic Encounters initiated by the Zapatista movement to the World Social Forums and other global campaigning networks, such as the Global Campaign to Reclaim Peoples Sovereignty, Dismantle Corporate Power and Stop Impunity. Yet, though we are all aware that only when we unite across the globe we can win against a global system of oppression, we far too often get caught up in the emergencies, contingencies and needs of our own struggles to be able to spare the necessary time to question how we can go beyond wishing success for the similarly oppressed.

It is essential that we understand our struggles as a common cause in order to accumulate the necessary forces to stand up against a system, which today is ever more blatantly showing its racist, exclusionary and oppressive nature. From the occupation of Palestine, to the devastating warfare all over West and Central Asia, to the rise of the right from Argentina to India and even in North America and Europe – we urgently need to identify our common ground and how to bring our efforts together into a powerful movement for land and resource rights, equality, self-determination and governing structures that respond to the people’s needs.

Remembering Fidel Castro’s legacy means reflecting on Cuba’s central contribution to the development of internationalism; today it is our responsibility to build an effective internationalism of the twenty-first century.

* Maren Mantovani is the coordinator for international relations of the Palestinian Stop the Wall Campaign and the Palestinian Land Defense Coalition

First published by: Afro-Middle East Centre at: https://www.amec.org.za/palestine/item/1512-tricontinental-solidarity-and-palestine-today.html

[1] de la Torre, Lopez and Fernando, Carlos (2014). Encuentros solidarios en epocas revolucionarias. La revolucion cubana y el Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional ante la causa palestina [Solidarity meetings in revolutionary times. The Cuban Revolution and the Sandinista National Liberation Front before the Palestinian cause]. CLACSO (Latin American Council of Social Sciences). https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/becas/20141202041539/ensayoclacso.pdf.

[2] Azambuja, Carlos (2005). ‘As origens da Tricontinental de Havana’ [‘The Origins of the Tricontinental of Havana’]. https://www.heitordepaola.com.br/imprimir_materia.asp?id_materia=3960.

[3] Oron, Yitzhak (ed.) (1961). Middle East Record, Vol 2. Tel Aviv: The Reuven Shiloah Research Center, Tel Aviv University. https://books.google.com.br/books?id=vzZ71Eh5QvMC&pg=PA45&lpg=PA45&dq=AAPSO+Gaza+1961&source=bl&ots=uE-35Tu8J5&sig=Sd0c93wN_7HYn6q_vDGtUOJQaIs&hl=pt-BR&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjg7J2R7eDKAhVJipAKHUiQAUIQ6AEIHzAA#v=onepage&q=AAPSO%20Gaza%201961&f=false.

[4] ‘Declaracion General de la Primera Conferencia Tricontinental (1966)’ [‘General Statement of The First Tricontinental Conference (1966)’]. https://constitucionweb.blogspot.ro/2014/06/declaracion-continental-de-la-primera.html.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Guevara, Ernesto Che (1967/1999). ‘Crear Dos, Tres…Muchos Vietnam’ [‘Create Two, Three…Many Vietnams’]. https://www.marxists.org/espanol/guevara/04_67.htm.

[7] de la Torre and Fernando (2014). https://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/becas/20141202041539/ensayoclacso.pdf.

[8] Othman, Haroub (2005). ‘Africa’s solidarity with Palestine’. Paper presented at the International Conference on ‘Vision of Bandung After 50 Years’, Cairo, 1–3 March. https://www.aapsorg.org/en/vision-of-bandung-after-50-years/541-africas-solidarity-with-palestine.html.

[9] (2016). ‘BRICS movement gathering momentum’, Business Standard, 11 October. https://www.business-standard.com/article/news-ani/brics-movement-gathering-momentum-116101100062_1.html.

[10] International Trade Statistics 2015. WTO (World Trade Organization). https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/its2015_e/its2015_e.pdf.

[11] (2011). ‘Israeli Exports’. https://disarmtheconflict.wordpress.com/israeli-arms/israeli-exports.

[12] Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. https://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/html/export_values.php.

[13] Cohen, Gili (2016). ‘Defense Ministry Official: Israel, Like Other Countries, Exports Arms Not Only to Democracies’, Haaretz, 20 June. https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.726097.

[14] The Israeli 'security' company ISDS, for example, since 1982, trained police and military forces for dictatorships in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and the Contras in Nicaragua. In the last decades it has entered the market of megaevents and holds a contract with the Rio 2016 Olympic Games. For many years, it has trained Rio de Janeiro's infamous military police to apply techniques in the favelas ‘just as we do in Gaza.

[15] Gross, Judah Ari (2016). ‘Records of Israeli arms sales during Rwandan genocide remain sealed’, Times of Israel, 12 April. https://www.timesofisrael.com/records-of-israeli-arms-sales-during-rwandan-genocide-to-remain-sealed; Konrad, Edo (2015). ‘The story behind Israel’s shady military exports’, +972, 22 November. https://972mag.com/who-will-stop-the-flow-of-israeli-arms-to-dictatorships/114080.

[16] SOS Kashmir (2011). ‘Indian Army using Israeli weapons in Kashmir’, Kashmir News, 15 July. https://soskashmir.wordpress.com/2011/07/15/indian-army-using-israeli-weapons-in-kashmir.

[17] Johnson, Jimmy (2010). ‘India employing Israeli oppression tactics in Kashmir’, The Electronic Intifada, 19 August. https://electronicintifada.net/content/india-employing-israeli-oppression-tactics-kashmir/8985.

[18] Simoes, Alexander (2014). Where does Israel export to? The Observatory of Economic Complexity. https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/visualize/tree_map/hs92/export/isr/show/all/2014 (accessed 26 December 2016).

[19] Leiderman, Leo and Mozerafi, Irit (2015). ‘Israeli trade with emerging markets requires selectivity’, Globes, 7 June. https://www.globes.co.il/en/article-israeli-trade-with-emerging-markets-requires-selectivity-1001042422.

[20] ‘Imports, by Country of Origin, excl. Diamonds’. https://www.cbs.gov.il/hodaot2016n/16_16_109t4.pdf.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Simoes, Alexander (2014). Where does Israel export to? The Observatory of Economic Complexity. https://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/visualize/tree_map/hs92/export/isr/show/all/2014 (accessed 26 December 2016).

[23] Ibid.

[24] ‘Glencore International AG’, Environmental Justice Atlas. https://ejatlas.org/company/glencore-international-ag.

[25] The case has become even more famous after the brutal assassination of Berta Caceres, leader of the movement opposing the dam, on 3 March 2016, but is definitely not the only example. For more see: de Boissiere, Philippa and Cowman, Sian (2016). ‘For Indigenous Peoples, Megadams Are “Worse than Colonization”’, Foreign Policy in Focus, 14 March. https://fpif.org/indigenous-peoples-megadams-worse-colonization.

[26] Methews, Rohan D (2011). ‘The Plachimada Struggle against Coca-Cola in Southern India’, ritimo, 1 July. https://www.ritimo.org/The-Plachimada-Struggle-against-Coca-Cola-in-Southern-India.

[27] (2015). ‘BDS marks another victory as Veolia sells off all Israeli operations’, BDS Movement, 1 September. https://bdsmovement.net/news/bds-marks-another-victory-veolia-sells-all-israeli-operations.

[28] (2016). ‘UN World Food Programme Drops G4S’ BDS Movement, 6 December. https://bdsmovement.net/world-food-program-drops-g4s.

[29] Richard Norton-Taylor, Britain is at centre of global mercenary industry, says charity, The Guardian, 3 February 2016,

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/feb/03/britain-g4s-at-centre-of-global-mercenary-industry-says-charity

[30] Steve Horn, Security Firm Guarding Dakota Access Pipeline Also Used Psychological Warfare Tactics for BP, Desmog Blog,13 September, 2016 https://www.desmogblog.com/2016/09/13/g4s-dakota-access-pipeline-human-rights-bp

[31]www.stopmekorot.org

[32] (2014). ‘The agreement with Mekorot in La Plata (Argentina) has been suspended!’ Palestinian Grassroots Anti-apartheid Wall Campaign, 7 March. https://stopthewall.org/2014/03/07/agreement-mekorot-la-plata-argentina-has-been-suspended.

[33] Khadse, Ashlesha (2016). Dairy and Poultry in India – Growing Corporate Concentration, Losing Game for Small Producers. https://globalforestcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/india-case-study.pdf.